Are you solving the biggest possible problem in your market?

I’ve been reflecting recently on a pattern I see constantly in my work with early-stage teams. The biggest threat to a startup usually isn't technical failure or execution risk—it’s the expenditure of finite resources on problems that customers do not desperately need solved.

We all talk a lot about "Product-Market Fit," but I believe we need to back up a step and talk about "Problem-Validation." Specifically, we need to address the dangerous illusion that existing in a "hot market" is enough to guarantee success.

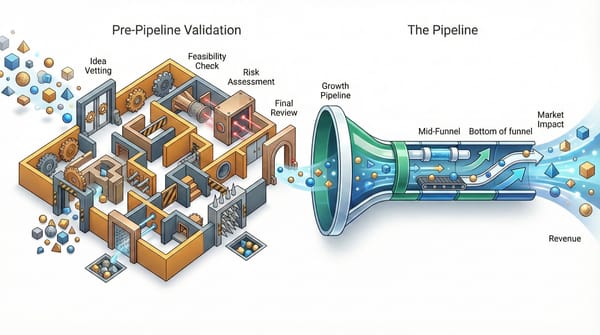

We need to distinguish between finding a general market (the "Mountain") and finding the specific, profitable ore vein IN that mountain. Too often, we validate the mountain—"Healthcare is growing," "Generative AI is the future," or "Cybersecurity is essential"—and assume that any solution we build on that mountain is necessary.

This is the "Tar Pit." It is treacherous precisely because the general market is valid. We deceive ourselves into believing that because the sector is growing, our specific solution is a "must-have." But within any massive market, there are thousands of problems. Most are lukewarm. Only a few are white-hot.

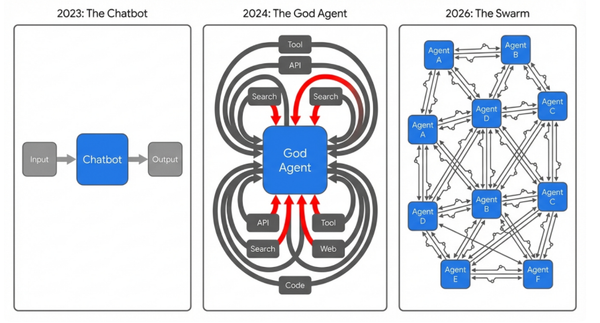

The Micro-Pivot: Same Product, 10x Opportunity

Here is the critical insight that often gets missed: You can build the exact same technology, but by solving a slightly different problem or targeting a slightly different stakeholder, you can change your outcome by 10x.

We see founders grinding away, trying to sell a tool to a mid-level manager who thinks it’s "cool" but has no budget. Meanwhile, one degree to the left, there is a Vice President facing a compliance audit who would pay ten times the price for 50% of the same functionality.

Finding this "white-hot center" often doesn't require a total restart. It requires a micro-pivot. It requires searching for the specific node in the network where the cost of inaction is highest. We need to stop asking "Could someone use this?" and start asking "Who will get fired if they don't use this?"

The Urgency Spectrum: Are We Selling Vitamins or Chemotherapy?

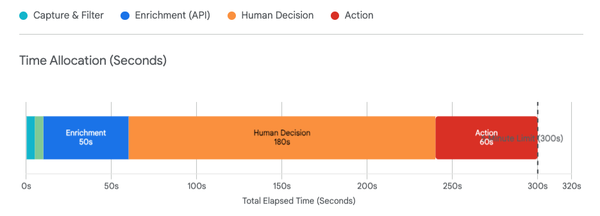

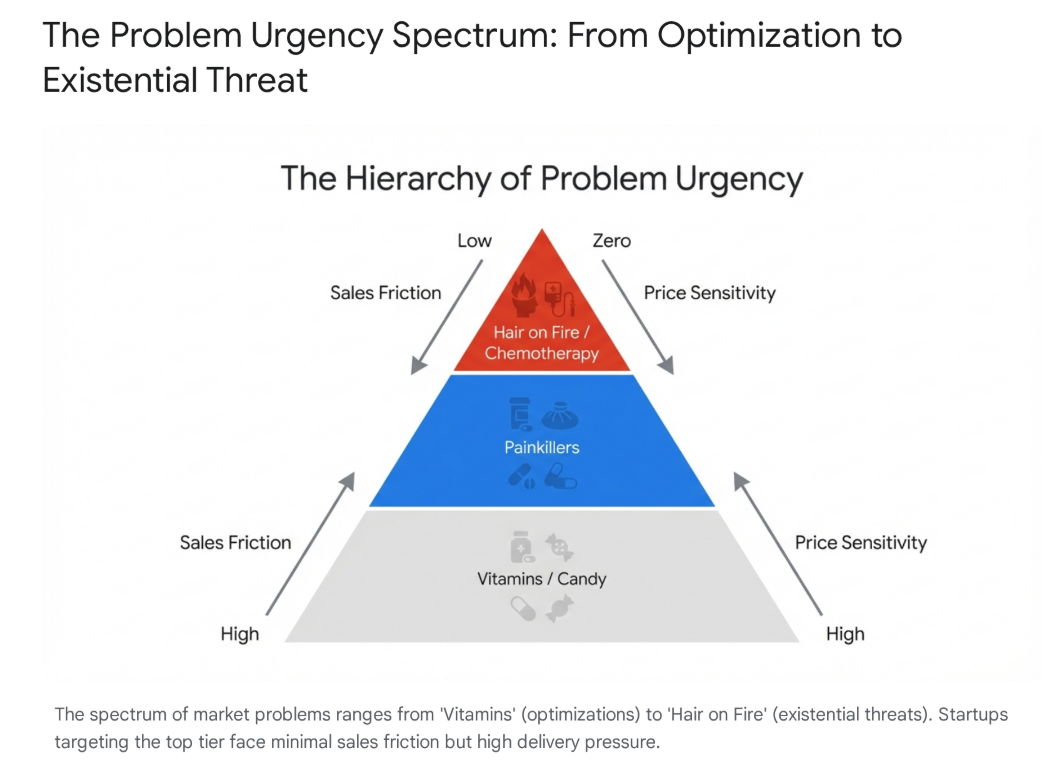

To be brutally honest with our roadmaps, we need to categorize our solutions into one of three buckets. This isn't just marketing semantics; it defines the economics of our business.

- Vitamins (Optimizations): These are "nice-to-have" improvements. They appeal to a user’s desire for efficiency, self-improvement, or long-term health. But like skipping a daily vitamin, the biological feedback loop is weak. If you skip it, nothing happens immediately. Consequently, sales cycles are long, churn is high, and price sensitivity is extreme because the user must be "educated" on why they need it.

- Painkillers (Relief): These address an active discomfort. The user knows they have a headache and wants it gone. The sales cycle shortens because the customer is already aware of the symptom.

- Chemotherapy (Survival): This is the standard we should aim for. Here, the cost of inaction is existential. The business will close, the executive will be fired, or the company will face a regulatory shutdown. In this zone, price elasticity collapses to near zero. The customer isn't "shopping"; they are rescuing themselves.

The "Bucket of Dirt" Reality Check

Michael Seibel (Y Combinator) uses a visceral metaphor that cuts through the noise: If your friend is standing next to you with their hair on fire, and you have a bucket of water, they aren't going to ask if the water is purified or if the bucket is a nice color. They just want the fire out.

This concept leads to the "Irrelevance of Quality" thesis. If you are embarrassed by your MVP, but the customer is ripping it out of your hands to use it, you have validated the problem. Conversely, if you build a polished product and customers offer polite praise ("This looks great, let me talk to my team") but no usage, you are likely in the vitamin trap.

When the pain is real, customers have a high tolerance for friction in the solution because the friction of the problem is infinitely higher. They will accept a "bucket of dirt" if it puts the fire out. If they are demanding bespoke features and polish before they sign, their hair isn't on fire.

Three Lenses to Validate Urgency

To ensure we aren't deceiving ourselves with "polite" customer interest (what Steve Blank calls "Validation Theater"), it’s worth looking at our problems through three distinct lenses employed by the best in the business.

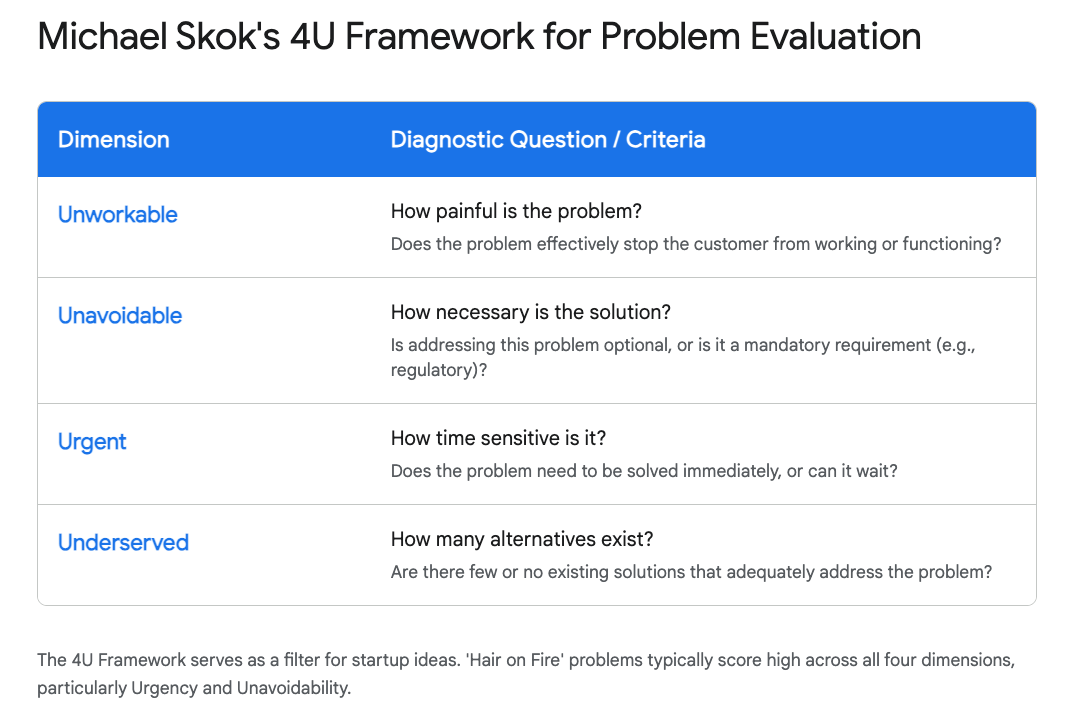

1. The "4U" Audit (Credit: Michael Skok)

Before committing engineering resources, we can conduct a diagnostic audit by scoring the problem against these four criteria. If we miss one, we are likely building a commodity.

- Unworkable: Is their current situation fundamentally broken? This goes beyond "inefficient." Unworkable means the system is freezing, the data is corrupted, or the process is physically impossible to complete at scale.

- Unavoidable: Is the problem mandatory? Many inefficiencies are annoying but avoidable (e.g., "I can just ignore the messy file system"). An unavoidable problem is often externally mandated by law, compliance, or the basic physics of the business (e.g., payroll must be met).

- Urgent: Is the problem time-bound? Urgency is the time dimension of pain. If a problem can be solved "next quarter," it is not hair-on-fire. It must be solved now.

- Underserved: Are there zero valid alternatives? A problem may be urgent and unworkable, but if a cheap, "good enough" solution exists (like Excel), you are fighting the "Status Quo" competitor. The opportunity exists only where the current solutions are nonexistent or toxic.

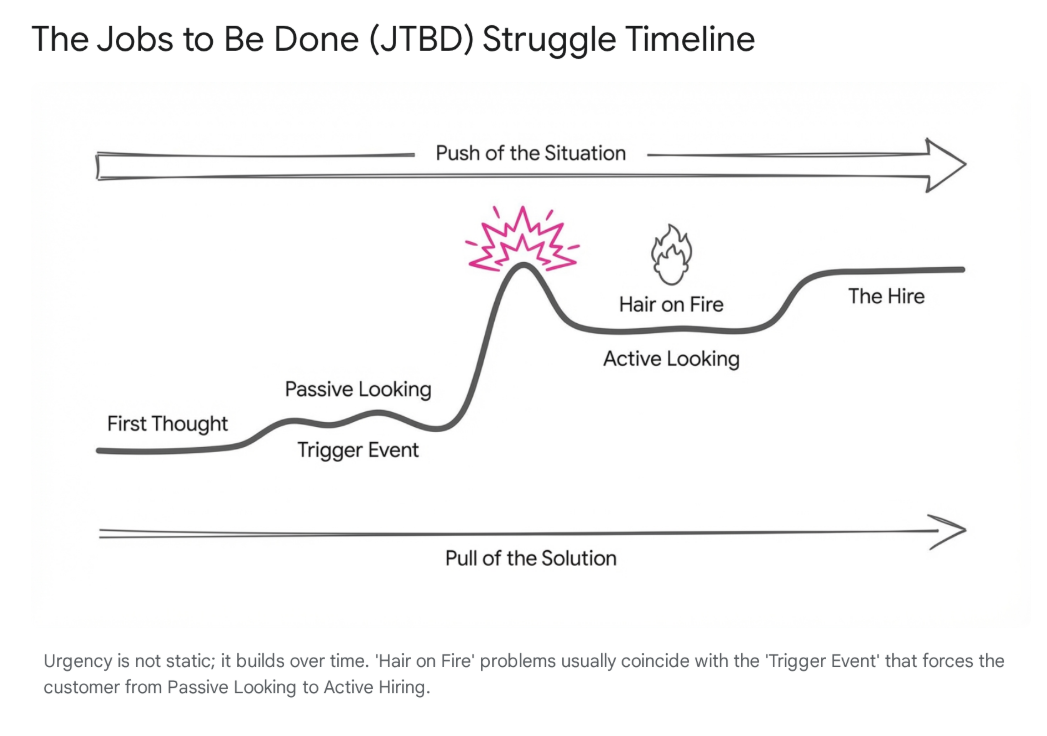

2. The "Switching" Trigger (Credit: Bob Moesta & Steve Blank)

As marketing and product leaders, we often focus on demographics. But Bob Moesta (creator of Jobs to Be Done) argues we should look for the timeline of the struggle.

People don't buy because they are "35-year-old males in tech." They buy because of a specific Trigger Event.

We need to identify the specific moment that pushes a buyer from "Passive Looking" (aware but tolerating the status quo) to "Active Looking" (frantically searching). Steve Blank suggests we should be able to write a "Crisis Memo" from the perspective of our customer's CEO, articulating exactly why the current situation is an existential threat. If we can't name the trigger event—the fine, the crash, the breakup—we are likely selling to people who don't yet know they are sick.

3. "Skin in the Game" (Credit: Alberto Savoia)

This is the toughest test for sales and founders. Alberto Savoia warns against trusting "Opinions" (talk) and instead demands "Data" (action). He suggests using a Validation Ladder to measure the true value of prospect interest:

- The Compliment (Score: 0): "That sounds like a great idea." (This is a false positive).

- Low Signal: They give you their email or contact info.

- Medium Signal: They give you their time (attending a 30-minute demo) or their reputation (intro to a boss).

- High Signal (The Gold Standard): They give you their money.

If a prospect won't give you a deposit or a strong, performance-based Letter of Intent (LOI) before the product is built, the problem likely isn't urgent enough. We must look for the "Development Partner" LOI, where a customer agrees to pay—or even pays a premium—to influence the roadmap because they are desperate for the solution.

The Bottom Line: Avoiding the "Tar Pit"

Dalton Caldwell calls the space where good founders die the "Tar Pit"—ideas that seem logical (e.g., "A social network for neighbors") but have no urgency.

It’s worth gathering your leadership team to ask: Do we have a hair-on-fire problem, or are we trying to educate the market on why they need a vitamin?

If the answer is the latter, we don't necessarily need to scrap the company. We may just need to pivot the application of our technology.

We need to keep searching until we find the crisis that makes our solution indispensable. We might be sitting on a goldmine, but digging in the slightly wrong spot.

Thanks for reading.

Troy