The "Horizontal Trap": Why aiming for everyone ensures we hit no one

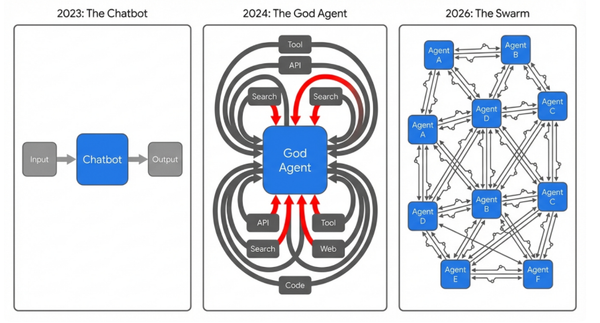

We see this constantly with ambitious founders, particularly in the current wave of platform shifts. They build a powerful technology—whether it’s a new developer platform, a data infrastructure tool, or yes, the current wave of Agentic AI—and they fall into a state of strategic paralysis. Because their product can theoretically serve any industry, they feel compelled to market it to every industry.

There is a deep fear of missing out (FOMO) here. Founders worry that if they define themselves too narrowly (e.g., "We serve mid-market CFOs handling multi-currency reconciliation"), they are leaving millions on the table. They want to be the "Platform for X" or the "Operating System for Y."

But the reality is the exact opposite. By trying to be everything to everyone, they end up being nothing to anyone.

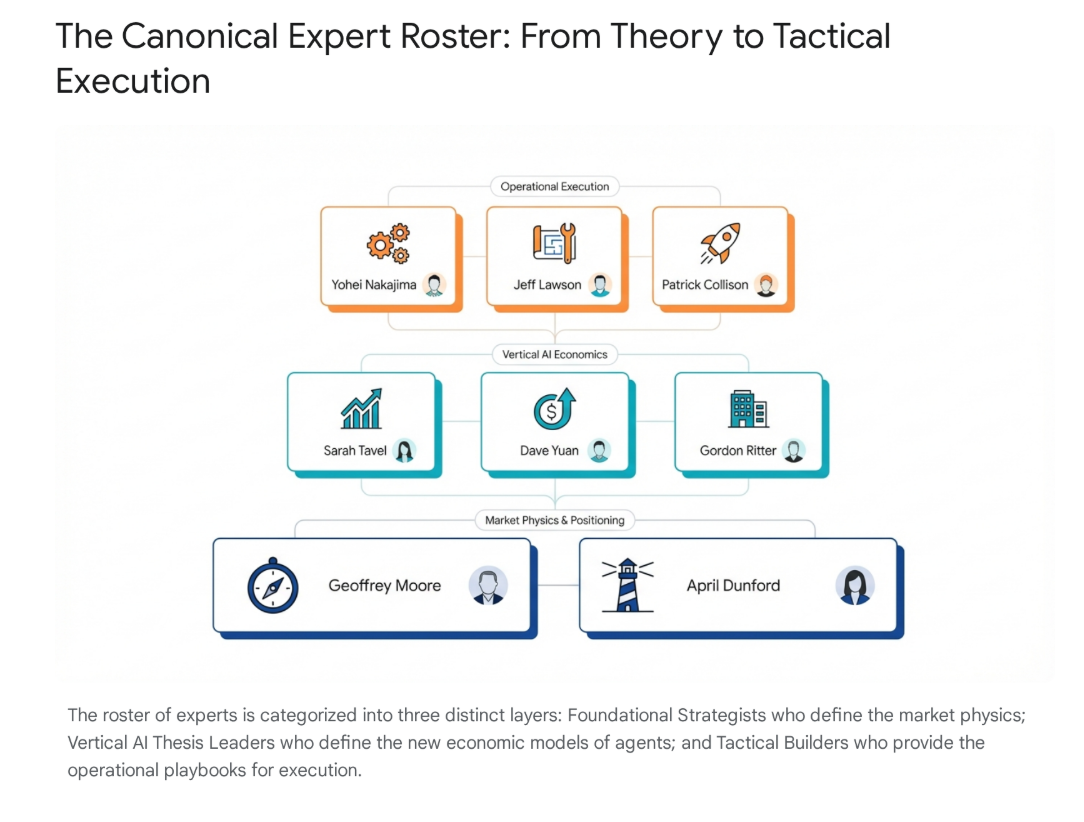

I’ve been revisiting the canonical research on this topic to better support my clients. The consensus from the world’s leading market strategists—from Geoffrey Moore to April Dunford—is that "going vertical" isn't a limitation; it is the only mechanics by which a horizontal platform actually succeeds.

Here is a comprehensive breakdown of the "Lead Pin" strategy, synthesizing insights from every major thought leader in the space.

1. The Physics of the "Lead Pin" (Geoffrey Moore)

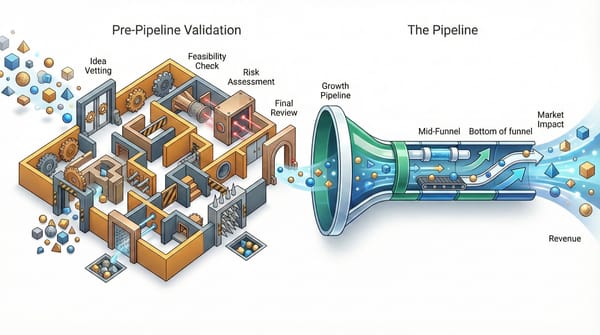

We often forget the core lesson from Geoffrey Moore’s Crossing the Chasm. He argues that the way to dominate a large market is not to attack it on a broad front, but to focus all energy on a single "head pin"—a specific niche that we can dominate completely.

Moore explains the fundamental disconnect between the "Visionaries" (early adopters) and the "Pragmatists" (the mainstream market). Visionaries will buy "potential"; they are willing to glue things together themselves. But pragmatists only buy solutions to specific problems. They need a "Whole Product"—not just the core software, but the integrations, the support, the standards, and the verified workflows that make it work out of the box.

The "Whole Product" Dilemma: If we try to sell a general "optimization platform" to HR, Sales, and Engineering simultaneously, we will fail. Why? Because the "Whole Product" for HR (compliance, Workday integration) is totally different from the "Whole Product" for Engineering (Jira integration, CI/CD compatibility). A startup simply cannot build three different "Whole Products" at the same time. You dissipate your energy and fail to satisfy anyone.

The Litmus Test: Moore gives us a strict definition for a valid segment to act as that first "Lead Pin." It’s not just "Developers" or "Small Business." A true segment consists of buyers who:

- Have the same specific problem.

- Talk to each other.

This second point is crucial. If a doctor in Boston buys our software, does a doctor in Seattle care? If they don't reference each other, they aren't a segment. Without that word-of-mouth momentum, we are forced to buy every single customer individually, which destroys our unit economics. We need a segment where, once we knock over the first pin, the rest fall because they trust the reference of the first.

2. Positioning: The Context Trap (April Dunford & Anthony Pierri)

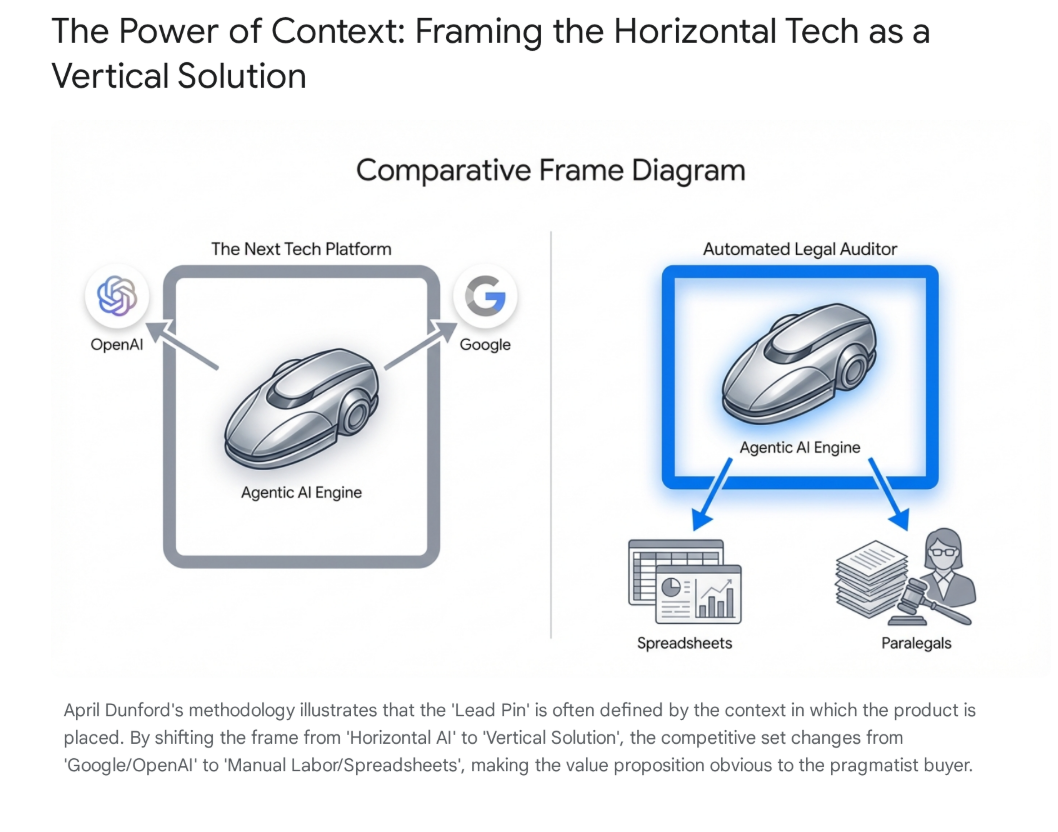

One of the biggest reasons startups fail to gain traction is that they position themselves in a context where they can't win. April Dunford calls this the "Context Trap." Positioning isn't about catchy taglines; it's about defining the market frame of reference.

The "Movie Opening Scene" Analogy: Dunford compares positioning to the opening scene of a movie. It answers the big questions: Where are we? Who are these people? How should I feel? If a startup creates the wrong context—for example, positioning themselves as "The World's Best Automation Platform"—they invite direct comparison to Microsoft, Google, or massive incumbents. That is a losing battle. The context is too big, and the competitors have trillion-dollar balance sheets.

However, if that same company shifts the context to "The Automated Audit Defense for Healthcare," the competition changes instantly. Now, they aren't competing with Microsoft; they are competing with "Excel spreadsheets," "hiring an intern," or "getting fined." We can win that battle.

The "Status Quo" Enemy: Dunford reminds us that in B2B sales, our biggest competitor isn't another startup; it’s "No Decision." Buyers stick with the status quo because the general solution sounds too risky or complex. By narrowing the context to a specific pain point, we make the decision safe.

Anthony Pierri adds a tactical layer to this: unless a founder explicitly chooses a "Positioning Anchor" (a specific job role or vertical), they will default to generic, horizontal messaging that lands with no one. We need to help our teams brave the discomfort of excluding 90% of the market in their messaging so they can actually close the remaining 10%.

3. The Economic Imperative: Survival & Outcomes (Tavel, Evans, McCormick)

Beyond positioning, there is a hard economic reason to narrow focus. We are entering an era where horizontal capabilities (like LLMs or cloud compute) are becoming commodities owned by hyperscalers.

Selling Work, Not Efficiency (Sarah Tavel): Tavel at Benchmark argues that the old SaaS model of selling "efficiency" (seats) is dead. The new model is "selling work" (outcomes). You don't sell a tool to help a lawyer; you sell the drafted contract. To do this, you must understand the vertical so deeply that you can guarantee the outcome.

The Only Defense Against Giants (Benedict Evans): Evans warns of "elite capture," where horizontal layers are dominated by the giants (Microsoft, Google). The only way for a startup to survive is vertical integration—owning the specific workflow and proprietary data that the giants can't access.

Eating the "Real Economy" (Packy McCormick): McCormick takes this further, suggesting that this "vertical wedge" is how software finally eats "atoms"—the physical world industries like logistics, bio, and manufacturing. These sectors resisted horizontal SaaS, but they will yield to vertical solutions that solve their messy, physical-world problems.

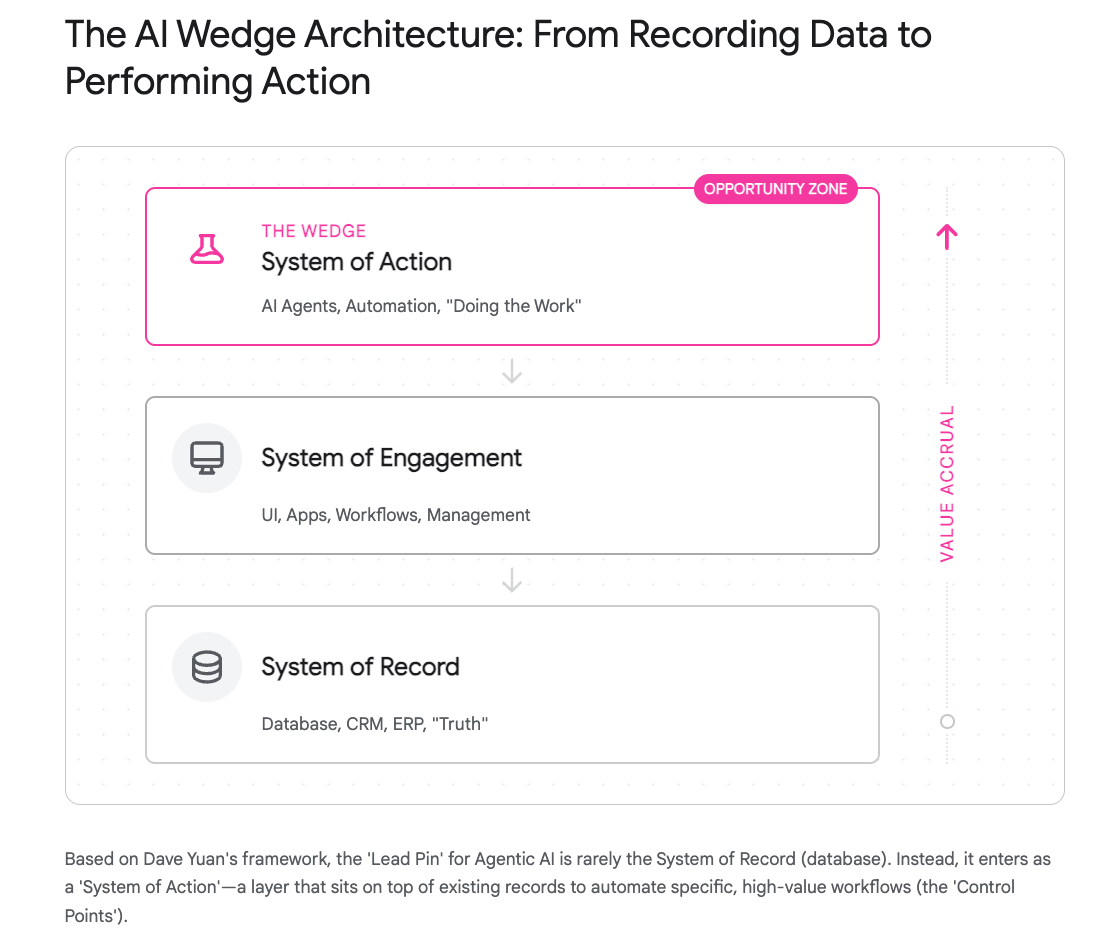

4. Identifying the Entry Point: Control Points & Coaches (Yuan, Ritter, Saper)

A common question we hear from technical founders is, "Okay, we’ll narrow down, but where do we start? Which pin do we hit?"

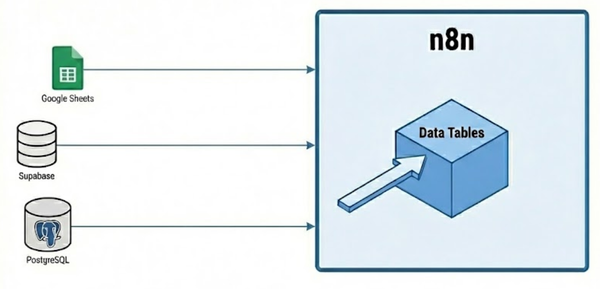

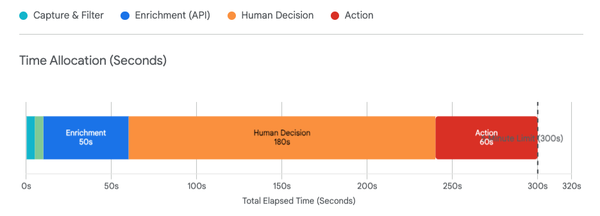

The System of Action (Dave Yuan): Yuan advises against trying to replace a company’s "System of Record" (like their massive ERP or CRM) on Day 1. Instead, look for the "System of Action"—the mission-critical workflows that sit on top of those databases. Find the specific, high-friction step where the "Hero User" is drowning in manual drudgery (e.g., the specific reconciliation process that keeps the CFO awake at night).

The Coaching Network (Gordon Ritter & Jake Saper): Ritter and Saper at Emergence Capital offer a brilliant alternative wedge: The "Coaching Network." Instead of trying to replace the human (which is scary and high-liability), the wedge is augmenting them. You build a system that observes the best workers and "coaches" the rest. This human-in-the-loop approach allows you to enter conservative verticals (like healthcare) where full automation is a non-starter.

5. Practical Execution: Four Paths to the Wedge

Finally, how do we actually execute this? History and modern practitioners give us four distinct playbooks.

Path A: The "Developer-First" Wedge (Lawson, Collison, Foster)

Twilio (Jeff Lawson), Stripe (Patrick Collison), and Zapier (Wade Foster) are massive horizontal platforms now, but they started as razor-thin wedges.

- Twilio didn't sell "Enterprise Telecom Infrastructure"; they sold an API to developers who wanted to send a text.

- Stripe solved the specific pain of "startup merchant accounts" and "ugly" banking compliance.

- Zapier marketed specific integration pairs (e.g., "Connect Typeform to Gmail"), not universal automation.

- Lesson: Find the "builder" in your vertical and remove all friction for them.

Path B: The "Agency-First" Wedge (Greg Isenberg)

For founders still searching for their vertical, Greg Isenberg suggests a pragmatic approach: Start as a Service Agency. Solve a specific problem (e.g., SEO) for a specific niche manually. As patterns emerge, build internal tools to automate yourself. Eventually, those tools become the product. This ensures you have a paying market before you write scalable code.

Path C: The "Micro-Wedge" (Yohei Nakajima)

Nakajima, creator of BabyAGI, advises against building grand platforms. Instead, build "single-purpose agents" (micro-wedges) that solve one tiny frustration (e.g., an "Outreach Agent"). Use community usage data to see what sticks, then double down. Let the market pull you into the lead pin.

Path D: The "Technical Reliability" Wedge (Swyx & Harrison Chase)

Swyx (Shawn Wang) and Harrison Chase (LangChain) focus on the technical reality. Swyx suggests finding verticals where "80% accuracy" is valuable (where a human is already in the loop and needs a draft). Chase argues the wedge into the enterprise is "RAG" (Retrieval Augmented Generation)—connecting the tool to the company's private data. You don't sell "AI"; you sell "Search Your Own Docs."

Summary

The message we need to drive home to our teams and portfolio companies is simple: Focus is not a retreat.

Narrowing our target market is actually an aggressive move. It allows us to concentrate our limited resources on a beachhead we can actually win, rather than dissipating our energy across a broad front we are guaranteed to lose.

As Geoffrey Moore famously noted, you do not cross the chasm by being a big fish in a big pond; you cross it by being the only fish in a tiny, carefully chosen pool, and growing from there.

To finding your lead pin

Troy